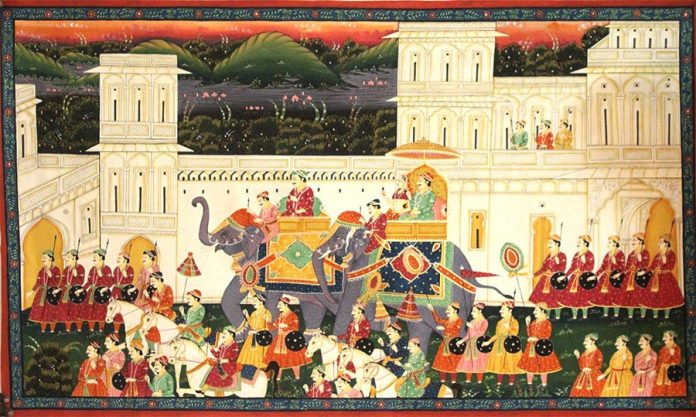

Babur (1526-30)

Babur victory in the first Battle of Panipat made him the Emperor of Delhi and the Founder of Mughal Empire in India. Before his death in December 1530 he defeated Rana Sanga in the Battle of Khanva fought in 1527.

Humayun (1530-40 & 1555-56)

Humayun succeeded his father Babur in 1530. Having been twice defeated by Sher Shah Suri, the Afghan leader, first in the Battle of Chausa and then in the Battle of Kannauj in 1540, Humayun fled away to Persia. After a lapse of 15 years, he restored his lost empire in 1555 with the help of Persian Emperor and died in 1556.

Sher Shah Suri (1540-45 A.D.): He ruled from 1540 to 1545. Grand Trunk Road was built by him. He died in 1545. Mohammed Ali Shah was the last ruler of this dynasty.

AKBAR (1556-1603)

Akbar (1556-1603) succeeded his father Humayun at the young age of 13 years. The emperor being minor, Bairam Khan worked as his regent. Hemu, the leader of Sur Afghans, who had captured Delhi and Agra, immediately after Akbar’s accession, was defeated by the Mughal army in the Second Battle of Panipat in 1556 and was subsequently slain by Bairam Khan. In 1560 he assumed personally the reins of government and dismissed Bairam Khan.

Akbar, by his diplomacy, won over all the Rajput princes except Rana Udai Singh of Mewar whose son Rana Pratap Singh like his father continued to defy the Mughal authority till his death in 1597 despite his defeat in 1567 in Battle of Haldighati. In pursuance of his policy of befriending Hindus, he married Jodhabai, the daughter of Raja BihariMaloi Jaipur who gave birth in 1569 to Salim, Akbar’s only son and heir.

A Sufi saint Salim Shah Chisti is believed to have blessed Akbar with the son In honour of the saint, he shifted his capital from Agra to Fatehpur Sikri where the saint lived. The imperial court remained there from 1570 to 1585. In 1581 he proclaimed a new religion named Din-e-llahi which although represented the good points of all religions, could not succeed. Birbal was the only Hindu who joined it. Akbar died in 1605 at Agra and was buried in a tomb built by the Emperor himself at Sikandra near Agra.

Jahangir (1605-1627)

Akbar’s son Salim succeed his father in 1605 as Jahangir. Guru Arjun of Sikhs who was an accomplice of Prince Khusro who revolted against Jahangir in 1606 was sentenced to death. In May 1611 Jahangir married Mirh-un-nisa, the widow of Sher Afghan, a Persian nobleman of Bengal. She was titled Nur-Jahan.

Shahjahan (1628-1659)

Shahjahan ascended the throne in 1628 after suppressing his brothers. Three years after his accession, Shahjahan beloved wife Mumtaz Mahal died. To perpetuate the memory of Mumtaz Mahal, Shahjahan built Taj Mahal at Agra in 1632-53. In 1636 the Emperor appointed his son Aurangzeb as the Viceroy of Deccan. Aurangzeb seized Agra in 1658 and later defeated all his brothers and imprisoned Shahjahan in 1659 who died in 1666 in the captivity of his son.

Aurangzeb (1659-1707)

Aurangzeb was crowned in 1659 as Alamgir. Religiously, he was most intolerant. He imposed Jaziya on non-Muslims. Jaziya was a coercive tax imposed on non-Muslims as a penalty for not embracing Islam.

Sikh revolt: Aurangzeb executed Tegh Bahadur, the ninth Guru of Sikhs in 1675 on his refusing to embrace Islam. His son Guru Govind Singh organised Sikhs in a militant band called Khalsa to avenge the murder of his father. Two of his own sons were put to death. Guru Govind Singh was murdered in 1708 by an Afghan in Deccan.

Relations of Aurangzeb with Marathas: Shivaji, the Maratha leader was another powerful enemy of Aurangzebs. Shivaji, seduced by Rajput ruler Jai Singh, went on the assurance of honourable peace terms to meet the Emperor at Agra in 1665 but was imprisoned. In 1666 Shivaji, however, managed to escape from the prison. In 1674 Shivaji was proclaimed a monarch. He died in 1680. He was succeeded by his son Sambhaji who was captured and executed by Aurangzeb and his son Sahu detained in the Mughal court.

Don’t Miss: