After the death of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan in 1898, the mantle of Aligarh Movement fell upon Nawab Mohsinul Mulk. The Indian Council Act of 1892, although an extremely feeble response to the aspirations of the Indian National Congress founded in 1885, made the Muslim leaders ponder over that the idea of loyalty to the raj propounded by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan was not adequate enough to obtain any considerable concessions for the Muslims from the British Government and that they must organise themselves politically for the fulfilment of their ideals. The permission for use of Hindi as the official language in the courts in U.P. by the Government in 1900 angered the protagonists of Urdu and provided the Muslim leaders an opportunity to organize themselves. They formed an association called Anjuman-e-Urdu at Lucknow with Mohsinul Mulk as the President. The Lieutenant-Governor, A. McDonell, viewed the agitation with misgivings and advised Nawab Mohsinul Mulk to abandon the Urdu agitation or resign from the secretaryship of the MAO College, Aligarh. The Urdu agitation, thus, ended abruptly.

Must Read: National Movement of India: 1920 to 1940

The partition of Bengal on the communal basis by Lord Curzon in 1905 cheered up the protagonists of the Muslim communalism as they thought that the English Government had accepted their separate identity and that the Muslims would be in the majority in the new province. The Viceroy advertised the new province as a Muslim province in a special meeting convened for the purpose at Dacca (Dhaka). The meeting fulfilled its purpose to an extent that the Government was able to obtain the support of a few Muslim leaders to their side. The best opportunity for causing irreparable cleavage between the two communities, however, came to the Government when a Muslim deputation headed by H.H. the Agha Khan waited upon the Viceroy in Simla in 1906, as a result of which separate electorate for the Muslims came to be introduced.

The seeds of the communal representation in the elected bodies were thus sown by the Government causing permanent cleavage between the two communities—the Muslims and the Hindus. It was a great day for the British imperialists. The Viceroy was very happy He had pulled back 62 million Muslims from joining the ranks of the “seditious opposition”. A delegate who met Lady Min to assured her, “His Excellency has kindled love in our hearts. We have always been loyal, but now we feel that the Viceroy is our friend.” The Indian Council Act of 1909, also known as Minto-Morley Reforms gave concrete shape to the assurances extended by the Viceroy to the Muslim delegation. This affixed the seal of Government approval on the theory of two nations for two separate communities, with distinct interests and outlook, which formed the basis of Aligarh Movement.

The grand success of the Simla deputation to Lord Minto emboldened the Muslim leaders to start a separate political organisation. Accordingly, Nawab Salimullah Khan sent invitations for a conference to be held at Dacca in December 1906. It met under the chairmanship of Viqarul Mulk who spoke in Urdu justifying the necessity for the establishment of a separate organization because unless the Muslims were united and were loyal to the British Government, they were in danger of being submerged by the enormous Hindu flood. The All-India Muslim League thus came into being on December 30, 1906, for the promotion of feelings of loyalty to the British, Government among the Muslims and protection and advancement of their political rights.

Read Also: National Movement of India: 1905 to 1920

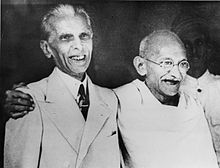

In its formative years, the Muslim League was not able to win popular support among the Muslims. Many prominent leaders of the community, like Maulana Shibli Naumani, Maulana Mohammad Ali, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad and Mohammad Ali Jinnah were opposed to it. In an article published in the Muslim Gazette of Lucknow, Maulana Shibli Naumani criticised the Muslim League vehemently, stating that the League, to keep up appearances, passed some resolutions of national interest, but everyone knew that it was a fake body.

Maulana Abul Kalam Azad published a news daily, Al Hilal, from Calcutta. It attempted to allay fears and imbibe a new spirit of hope and courage among Muslims. The transfer of the headquarters of the Muslim League from Aligarh to Lucknow and the annulment of the partition of Bengal in December 1911 helped the Muslim League leaders to free themselves from the domination of the British bureaucrats and paved the way for their entry into the mainstream of the national life. The result was the coming together of the Muslim League and the Indian National Congress. The two parties held their sessions in 1915, 1916 and 1917 at Bombay, Lucknow and Calcutta, respectively. The Presidents of the two parties had an exchange of views on national issues and many Congress leaders attended the sessions of the Muslim League. These gestures of goodwill brought about the Lucknow Pact in 1916. The Congress conceded the demand of the Muslim League for the separate electorate and the two parties agreed upon the number of seats to be reserved for the Muslims in various provinces. They also decided on the pattern of demands to be made to the British Government for the achievement of self-governing institutions and repeal of anti-people laws like the Arms Act, the Press Act and the Defence of India Act. ‘ This era of cooperation and fraternity between… the Congress and the League continued to grow unabated for many years. Presiding over the annual session of the Muslim League in 1918 at Delhi,

Fazlul Haq stated, “To me, the future of Islam in India seems to be wrapped in gloom and anxiety. Every instance of a collapse of Muslim power in the world is bound to have an adverse influence on the political importance of our community in India.” In 1919, the ulemas formed an association called the Jamiat-Ulama-i-Hind. It extended its full support to the demands of the Khilafat Conference and exhorted the Muslims to join the Non-Cooperation Movement. The Congress, the League, the Khilafat and the Jamiat-Ulama-i-Hind thus acted in unison and fought jointly against the Government. This was bound to create a great stir and unity in the country. For Mahatma Gandhi, it was a godsend opportunity to cultivate the Hindu-Muslim unity. He said, “If the Hindus wish to cultivate eternal friendship with the Musalmans, they must perish with them in the attempt to vindicate the honour of Islam.”

Fazlul Haq stated, “To me, the future of Islam in India seems to be wrapped in gloom and anxiety. Every instance of a collapse of Muslim power in the world is bound to have an adverse influence on the political importance of our community in India.” In 1919, the ulemas formed an association called the Jamiat-Ulama-i-Hind. It extended its full support to the demands of the Khilafat Conference and exhorted the Muslims to join the Non-Cooperation Movement. The Congress, the League, the Khilafat and the Jamiat-Ulama-i-Hind thus acted in unison and fought jointly against the Government. This was bound to create a great stir and unity in the country. For Mahatma Gandhi, it was a godsend opportunity to cultivate the Hindu-Muslim unity. He said, “If the Hindus wish to cultivate eternal friendship with the Musalmans, they must perish with them in the attempt to vindicate the honour of Islam.”

The Muslims and Hindus, therefore, vied with one another in defying the Government. Thousands cheerfully went to jail. They bore the rigours of the lathi charges with utmost calm. Lawyers abandoned the practice, teachers resigned service and students withdrew from schools and colleges. After the Chauri Chaura incident, Gandhiji called off the Non-Cooperation Movement. The Khilafat Movement also lost its relevance after the Khilafat was abolished in 1924. But these movements had certainly given a severe blow to the forces of communalism. The Muslim League lost much of its public appeal. But, unfortunately, there were communal riots after 1923 in the country and a communal Hindu body, the Hindu Mahasabha, emerged to work as a counterpoise to the Muslim League. It advocated sbuddhi and Sangathan, bound to cause anguish in the minds of other communities. The Hindu-Muslim unity achieved during the Khilafat and Non-Cooperation Movements thus proved to be too short lived because the roots of communal antagonism were very deep. But it overwhelmingly demonstrated that the British imperialism would have to pack up if the two communities—the Muslims and the Hindus—were united and fought together against foreign rule.

The Muslims and Hindus, therefore, vied with one another in defying the Government. Thousands cheerfully went to jail. They bore the rigours of the lathi charges with utmost calm. Lawyers abandoned the practice, teachers resigned service and students withdrew from schools and colleges. After the Chauri Chaura incident, Gandhiji called off the Non-Cooperation Movement. The Khilafat Movement also lost its relevance after the Khilafat was abolished in 1924. But these movements had certainly given a severe blow to the forces of communalism. The Muslim League lost much of its public appeal. But, unfortunately, there were communal riots after 1923 in the country and a communal Hindu body, the Hindu Mahasabha, emerged to work as a counterpoise to the Muslim League. It advocated sbuddhi and Sangathan, bound to cause anguish in the minds of other communities. The Hindu-Muslim unity achieved during the Khilafat and Non-Cooperation Movements thus proved to be too short lived because the roots of communal antagonism were very deep. But it overwhelmingly demonstrated that the British imperialism would have to pack up if the two communities—the Muslims and the Hindus—were united and fought together against foreign rule.

The Muslim League was split up in 1927 into two factions, one led by Sir Mohammad Shafee and the other by Mohammad Ali Jinnah. Both were unable to muster much support and were functioning as drawing room parties. In 1929, the Nationalist Muslims left the Muslim League to form a new party, the Nationalist Muslim Party. They met at Lucknow in 1931 under the chairmanship of Sir Ali Imam who declared, “If I were asked why I have such abiding faith in Indian nationalism, my answer is that without that India’s freedom is an impossibility. Separate electorate connotes negation of nationalism.” It was evident that the Muslim League was relapsing into oblivion in the national politics of the country, although Jinnah had attempted to give a dose of life to the League by enunciating his famous Fourteen-Point Programme to counter the Nehru Committee Report. He also worked hard to reorganise and consolidate the League. At the Bombay session of the League held in April 1936, Sir Syed Wazir Hasan stated in his presidential address, “In the higher interests of the country, I appeal for unity not only between Hindus and Muslims as such but also between the various classes and different political organisations.” He also enunciated a four-fold programme on whose basis a nationwide movement could be organised and various communities brought together through mutual confidence.

Don’t Miss: The Great Indian Leaders

All this changed for the worse with the formation of provincial ministries by the Congress in July 1937. The clouds of communalism began to gather fast and grow thicker on the skies. The Muslim League castigated the Congress ministries for alienating the Muslims of India more and more by pursuing pro-Hindu policies and making them feel that they could not expect any justice or fair play at their hands. It also whipped up its propaganda against the Congress and pinpointed the latter’s refusal to form the coalition ministries as the proof of its resolve to crush the Muslims.

The reports of the two League committees—the Pirpur Report in U.P. and Sharif Report in Bihar—listed various grievances and atrocities inflicted by the Congress ministries on the Muslims driving a wedge between the Hindus and the Muslims and strengthening the Muslim League. Thus, when in September 1939, the Congress ministries resigned in protest against their country being dragged into the Second World War without consultation and refusal of the British Government to declare the Indian independence, the Muslim League observed a “Deliverance Day” to celebrate the exit of the Congress ministries.

Events followed in quick succession. The Muslim League met in Lahore in March 1940 and passed a resolution that the Muslim-majority regions in the North-West and the Eastern zones of India may be constituted as “Independent States”. They later became the West Pakistan and the East Pakistan on August 14, 1947.

Also Read: Facts about World War 2

The originator of the idea of Pakistan was Sir Muhammad Iqbal (1873-1938) who made a plea for the creation of a Muslim-majority state at the Allahabad session of the Muslim League held in 1930. He declared himself as a Pan-Islamist with the mission of purging Islam of infidels. He enunciated, “I would like to see Punjab, North-West Frontier Province, Sind and Baluchistan amalgamated into a single state. Self-government within the British empire or without the British empire, the formation of a consolidated North-West Indian Muslim State appears to me the final destiny of the Muslims, at least of North-West India.” Rahmat Ali, a student at Cambridge, took the fancy to the idea and communicated it to the Muslim members of the Round Table Conference in London. But none took it seriously. His concept was that Punjab, N.W.F.P. (also known as Afghan Province), Kashmir, Sind and Baluchistan formed the national home of the Muslims called by him Pakistan by taking the initials of the first four and last part of the fifth.

At the Madras session of the Muslim League held in April 1941, Jinnah declared in his presidential address that they did not want a constitution of an all-India character with one Government at the Centre and that they were determined to establish the status of an independent nation. He thus made the creation of Pakistan the main plank of the League.

After the end of the Second World War, elections were held in which the Muslim League captured 446 seats out of a total 495 Muslim seats. When the Cabinet Mission visited India in March 1946, the League pressed its claim for the creation of Pakistan. The Mission rejected the demand and proposed grouping of the Provinces with A, B and C groups under a federation. The League gave a call for the “Direct Action Day” on August 16, 1946, to achieve Pakistan, on which day there were riots in Bengal to demonstrate that the Muslims would not be able to live together with the Hindus. As the Ministers of the interim Government led by Jawaharlal Nehru were being sworn in September 1946, the supporters of the Muslim League were raising slogans “Long Live Pakistan”. The League later joined the interim Government on October 20, 1946, but the two major parties were not working smoothly. The result was the partition plan put forward by Lord Mountbatten in June 1947. It divided the country into two separate dominions of India and Pakistan. Jinnah was the first Governor-General of Pakistan, sworn in on August 14, 1947. It was a day earlier to the date of our destiny, August 15, 1947, when we won our independence (But the same moment of time).

Must Read:

Rare Colour Video of 1947 Indian Independence