Table of Contents

- Introduction

- What is a Scientific Revolution?

- Pre-Scientific Thought: Natural Philosophy

- The Copernican Revolution

- The Galilean and Newtonian Synthesis

- The Chemical and Electromagnetic Revolutions

- The Thermodynamic Revolution

- The Relativity Revolution

- The Quantum Revolution

- The Information and Quantum Computing Age

- Kuhn’s Theory of Scientific Paradigms

- Interplay Between Technology and Scientific Revolutions

- Unfinished Revolutions and Open Challenges

- Conclusion

1. Introduction

Scientific revolutions are transformative shifts in scientific thinking that redefine how we understand the universe. These revolutions mark turning points that replace outdated paradigms with new theories that more accurately explain and predict natural phenomena. Understanding these milestones is crucial as we journey toward deeper knowledge in quantum physics and beyond.

2. What is a Scientific Revolution?

A scientific revolution involves:

- The overturning of established paradigms.

- The birth of new theories.

- Shifts in methodology, tools, and even philosophical outlooks.

According to Thomas Kuhn in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), scientific revolutions are non-cumulative and paradigm-shifting events in the history of science.

3. Pre-Scientific Thought: Natural Philosophy

Before formal scientific methods, natural philosophy merged speculative reasoning with rudimentary observations. Thinkers like Aristotle, Ptolemy, and Archimedes laid early foundations that were later challenged during the scientific revolutions.

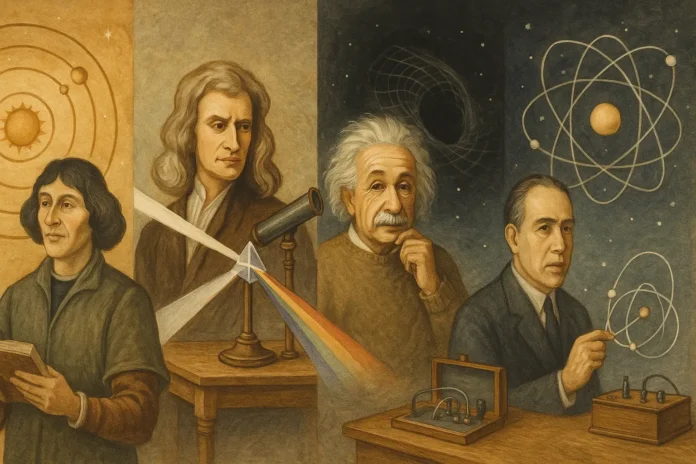

4. The Copernican Revolution

Nicolaus Copernicus proposed a heliocentric model in De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, where the Sun—not Earth—was the center of the universe. This directly challenged the long-accepted Ptolemaic (geocentric) model.

Johannes Kepler built on Copernicus’ model with three laws of planetary motion, derived from observational data:

- Kepler’s First Law (Elliptical Orbits):

The orbit of a planet is an ellipse with the Sun at one of the foci. - Kepler’s Second Law (Equal Areas):

A line joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time. - Kepler’s Third Law (Harmonic Law): \( \frac{T^2}{r^3} = \text{constant} \)

This revolution launched modern astronomy and set the stage for Newtonian physics.

5. The Galilean and Newtonian Synthesis

Galileo Galilei

Galileo combined experimentation with mathematical abstraction, laying down the principle of inertia and advocating for heliocentrism through telescope observations.

Isaac Newton

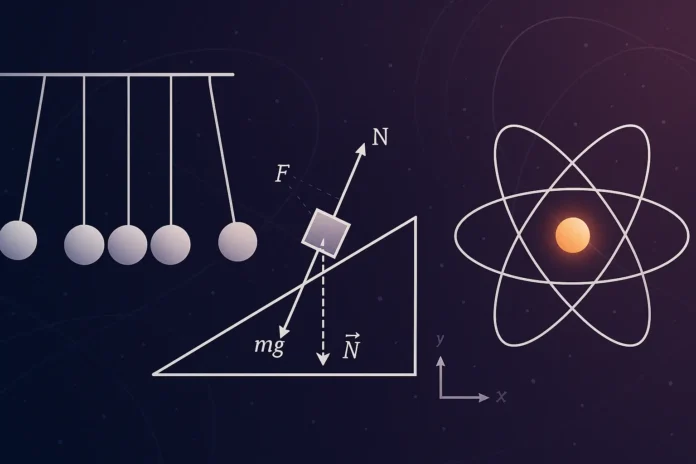

Newton’s contributions unified celestial and terrestrial mechanics through a set of universal laws.

- Newton’s Second Law of Motion: \( F = ma \)

- Universal Law of Gravitation: \( F = G \frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2} \)

Where:

- F is the gravitational force,

- G is the gravitational constant,

- \( m_1, m_2 \) are the masses,

- rr is the distance between them.

Newton’s Principia Mathematica laid down a deterministic framework that dominated physics for over two centuries.

6. The Chemical and Electromagnetic Revolutions

Chemical Revolution

Antoine Lavoisier formulated the Law of Conservation of Mass:

\[ \text{Mass}_{\text{reactants}} = \text{Mass}_{\text{products}} \]

This shifted chemistry from qualitative alchemy to quantitative science.

Electromagnetic Revolution

Michael Faraday discovered electromagnetic induction, while James Clerk Maxwell synthesized electricity and magnetism into a single framework.

Maxwell’s Equations in differential form:

\[ \nabla \cdot \vec{E} = \frac{\rho}{\varepsilon_0} \]

\[ \nabla \cdot \vec{B} = 0 \]

\[ \nabla \times \vec{E} = -\frac{\partial \vec{B}}{\partial t} \]

\[ \nabla \times \vec{B} = \mu_0 \vec{J} + \mu_0 \varepsilon_0 \frac{\partial \vec{E}}{\partial t} \]

These equations predicted the existence of electromagnetic waves, laying the groundwork for radio, radar, and modern communication.

7. The Thermodynamic Revolution

Driven by the study of heat engines, thermodynamics emerged as a distinct field.

First Law of Thermodynamics (Energy Conservation):

\[ \Delta U = Q – W \]

Where:

- \( \Delta U \) is the change in internal energy,

- Q is heat added,

- W is work done by the system.

Second Law of Thermodynamics (Entropy):

\[ \Delta S \geq 0 \]

Indicating that entropy in an isolated system never decreases.

These laws had profound implications in physics, chemistry, biology, and even cosmology.

8. The Relativity Revolution

Special Relativity (1905)

Einstein redefined the concepts of space and time:

- Time Dilation: \( t’ = \frac{t}{\sqrt{1 – \frac{v^2}{c^2}}} \)

- Mass-Energy Equivalence: \( E = mc^2 )\

Where:

- t is proper time,

- v is relative velocity,

- c is the speed of light.

General Relativity (1915)

Describes gravity as a result of spacetime curvature.

Einstein’s Field Equations:

\[ R_{\mu\nu} – \frac{1}{2} g_{\mu\nu} R + \Lambda g_{\mu\nu} = \frac{8\pi G}{c^4} T_{\mu\nu} \]

Where:

- \( R_{\mu\nu} \) is the Ricci curvature tensor,

- \( g_{\mu\nu} \) is the metric tensor,

- \( T_{\mu\nu} \) is the energy-momentum tensor.

General Relativity accurately predicts phenomena like gravitational lensing and black holes.

9. The Quantum Revolution

Quantum theory arose to explain phenomena classical physics could not, such as:

- Blackbody radiation

- Photoelectric effect

- Atomic spectra

Planck’s Quantization:

\[ E = h \nu \]

Where:

- \(E\) is energy,

- h is Planck’s constant,

- \( \nu \) is frequency.

Schrödinger’s Equation (Time-dependent):

\[ iℏ∂ψ∂t=H^ψi \hbar \frac{\partial \psi}{\partial t} = \hat{H} \psi \]

Where:

- \( \hbar \) is reduced Planck’s constant,

- \( \psi \) is the wavefunction,

- \( \hat{H} \) is the Hamiltonian operator.

Quantum mechanics introduced probabilistic interpretations and wave-particle duality, revolutionizing our understanding of reality.

10. The Information and Quantum Computing Age

Claude Shannon’s Information Theory (1948):

Defined bit as the fundamental unit of information and introduced entropy in communication:

\[ H(X) = – \sum_{i=1}^{n} p(x_i) \log_2 p(x_i) \]

Quantum Information:

Qubit: Can exist in superpositions:

\[ |\psi\rangle = \alpha |0\rangle + \beta |1\rangle\]

where

\[ |\alpha|^2 + |\beta|^2 = 1 \]

Quantum Gates: Operate as unitary transformations, e.g., Hadamard Gate:

\[ H = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ 1 & -1 \\ \end{bmatrix} \]

Quantum information theory now underpins advances in quantum cryptography, teleportation, and computing.

11. Kuhn’s Theory of Scientific Paradigms

Thomas Kuhn proposed that science advances via paradigm shifts:

- Normal Science – Routine work within an existing framework.

- Crisis – Accumulation of anomalies.

- Revolution – Emergence of a new theory.

- New Normal Science – A new paradigm becomes dominant.

This model explains why scientific revolutions are often resisted and how they reshape the scientific landscape.

12. Interplay Between Technology and Scientific Revolutions

Technology both enables and is driven by science:

- Telescopes → Astronomy

- Microscopes → Biology

- Accelerators → Particle Physics

- Lasers → Quantum Optics

Breakthroughs like quantum computers, LIGO detectors, and Fermilab experiments all emerged from tight feedback between theory and technology.

13. Unfinished Revolutions and Open Challenges

Some revolutions are ongoing or incomplete:

- Quantum Gravity: Unifying General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics.

- Dark Energy and Dark Matter: 95% of the universe is still unexplained.

- Arrow of Time: Why time flows in one direction.

- Consciousness and Measurement: Role of the observer in quantum theory.

These open questions point toward future revolutions in physics.

14. Conclusion

Scientific revolutions have repeatedly redefined humanity’s understanding of reality—from Newton’s clockwork universe to Einstein’s curved spacetime, and now quantum superpositions. Each new paradigm opened new technological and philosophical frontiers.

Understanding the history of these revolutions equips us to appreciate—and contribute to—the quantum transformations underway today.